Wings of the Chandra PSF¶

The Chandra PSF falls in two regimes: The shape of the core is set by quasi-specular reflection from low-frequency surface errors. This component is strongly peaked and dominates in the innermost few arcseconds (for an on-axis source). The outer part of the PSF has the shape of a powerlaw with a spectral index close to two and is caused by micro-roughness on the mirror surfaces. The Proposer’s Observatory Guide and a memo by T.J. Gaetz discuss this in a lot more detail. The memo is based on a very detailed analysis of a deep Her-X1 observation. In this test we replicate that observation in marx and SAOTrace simulations.

In the memo, T.J. Gaetz goes to great lengths to separate the effect of the intrinsic Chandra PSF on the data from other influences such as the ACIS contamination. When we compare data and marx simulation below, we chose a somewhat simpler approach. We perform steps to mitigate the impact of other astrophysical sources (which are not part of the marx simulation) and background (which is not part of the marx simulation). On the other hand, we just compare the observed count rates with no correction for the ACIS contamination, dithering near chip edges etc. because those effects are included in both the observed and the simulated data.

Read the code for this test to see all details of the data extraction, but here are the most important points:

The source is heavily piled-up, thus the source spectrum is taken from the read-out streak.

Because of pile-up in the data, all fitting is restricted to radii above 15 arcsec.

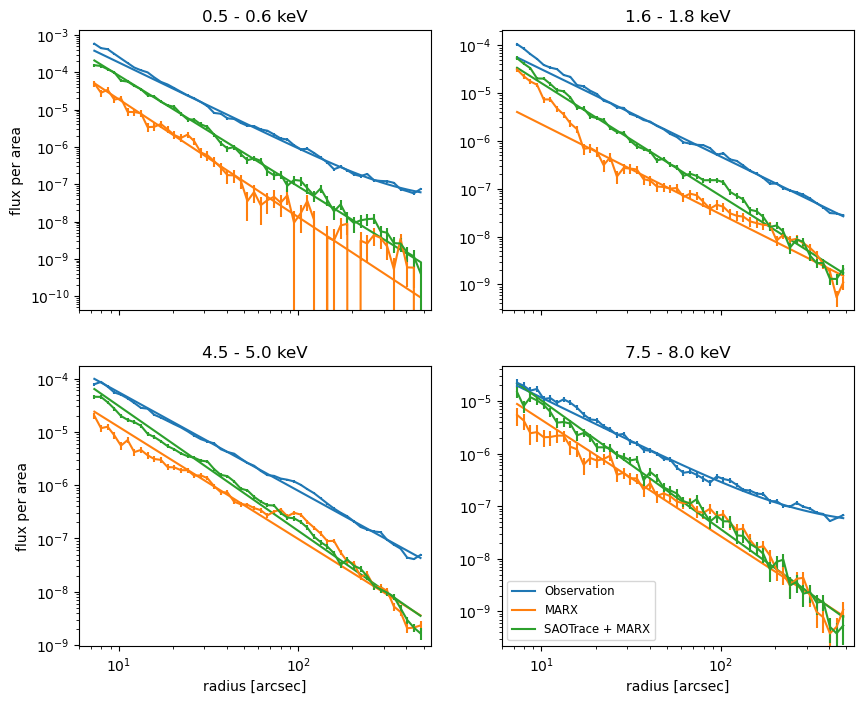

The flux in the scattering halo drops as a powerlaw with increasing distance from the source. In these plots, we should look only at the slope, not the absolute normalization because the total count rate is uncertain in the observation due to the severe pile-up, so the input flux to the simulations might be lower than the true flux.

The plots show the data (with purely statistical uncertainties) and powerlaw fits. Due to the background that is part of the observations but not the simulated data, the powerlaw flattens out for the observed data at high and low energies, where the total count number is low and thus the background more important. We add a constant to the powerlaw model to account for this. SAOTrace simulations produce a fairly smooth powerlaw similar to the observations. The pure marx simulations have much larger deviations due to marx’s simplified mirror model.

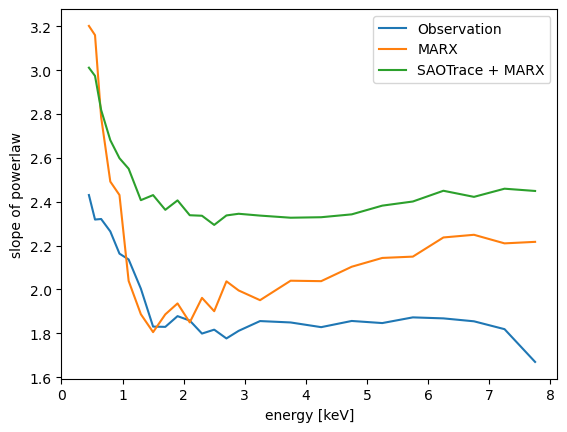

The surface brightness falls off with increasing distance from the source position as a powerlaw. The exponent of this powerlaw depends on the photon energy as shown in the figure. If spectra are extracted in the scattering halo the observed spectrum will thus change with distance from the source. For the observed data, the low energy end (below about 1 keV) has to be taken with a grain of salt. We applied a correction for the ACIS contamination in the data reduction, but the distribution of the contaminant over the detector area is not well known, leading to systematic uncertainties. For energies above 5 keV, the outer mirror shell does not contribute much effective area any longer. This shell has the roughest surface, which explains why we observe steeper powerlaw slopes for higher energies. Both the marx and the SAOTrace mirror model also have energy dependent exponents.

Summary¶

Both marx and SAOTrace simulations reproduce the wings of the Chandra PSF reasonably well. There are differences in the details, but there is also some uncertainty in the observed data, which, unlike the simulations, contains background events and some detector effects not modeled in marx. It is important to remember though that we study the wings out to several arcminutes here. In all but the brightest sources on the sky, the wings will be undetectable this far out, simply because the total count rate out in the wings is orders of magnitude lower than the in the center of the PSF and will be lost in the background.